Rubaiya Ahmad of Obhoyaronno asks activists to educate themselves, seek expert insights, and lead their animal welfare efforts with science and facts rather than feelings.

The reopening of St. Martin’s Island this November, after a nine-month break from tourists, is less a moment of celebration and more a point of intense debate over its environmental security. The closure itself was an act of extreme environmental diplomacy, reportedly masterminded by the formidable Syeda Rizwana Hasan, who ran her brief with an iron fist, managing to keep the public out.

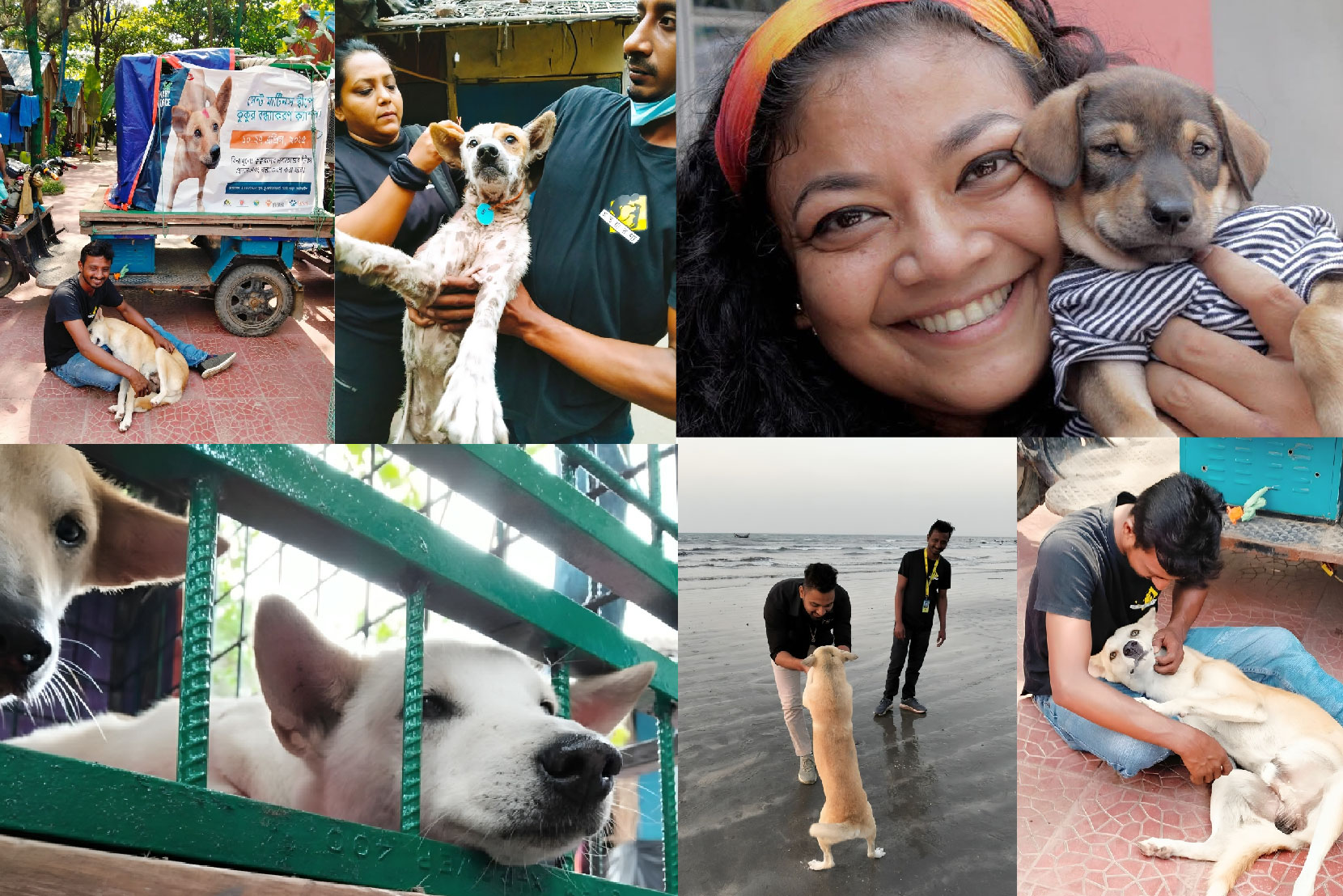

To gauge the island’s true situation beyond official press releases, we sought out Rubaiya Ahmad, the founder of animal welfare foundation Obhoyaronno, who has perhaps been on the island more than anyone else during the lockdown. Her team was granted access for a crucial survey back in January, a two-week-long Canine Population Management drive in April, and most recently, she toured the island with a team of botanists, geologists, and soil experts to check its vital signs. Simply put, she has the receipts.

I met Ahmad for a quick chat at her Dhaka residence. Her dog, Bear, offered a brief, courteous inspection at the door before quickly losing interest and retreating inside the house. I tried to be polite and decline the tea. She insisted. “Try it, it’s really good.” So I conceded. As the rich, dark brew arrived, we settled in. The conversation immediately jumped past small talk, turning to St. Martin’s. The government is preparing to reopen the island for tourism, a decision Rubaiya Ahmad views with profound, existential dread.

“I will be blunt,” she stated with conviction. “If I were in power, I would shut down the island for tourism completely and permanently.”

To understand this, we must understand why the travel ban was necessary in the first place. It was an emergency intervention necessitated by a spiralling ecological crisis. The sheer volume of tourists (up to 8,000 per day) had overwhelmed the tiny coral island, accelerating the destruction of its marine ecosystem and biodiversity.

The most visible disasters were the rampant, unregulated construction of illegal multi-storey hotels by external businessmen and the total failure of waste management, which turned the coastline into a dumping ground. The island was closed because mass tourism had become a lethal pollutant, and the government had run out of less drastic options to halt its demise.

Ahmad confirms the damage is real, but hints at hope, citing a recent government-appointed team of experts, including soil specialists, geologists, and botanists from Dhaka University, who found subtle but hopeful signs of ecological recovery after less than a year of reduced tourism. “In a year, you won’t see a dramatic difference, but the experts saw things we might miss,” she says. “The Keya field has regrown. Crabs are reappearing, and their small homes are more pronounced. It’s early days, but the island is breathing again.”

This travel ban has, predictably, been met with a strong pushback. News reports focused on the plight of islanders, barely making a living, with locals supposedly being forced to sell their land to resort owners just to eat. The common narrative paints a picture of a general economic crisis.

For Ahmad, this current crisis is deliberately misrepresented. While headlines focus on struggling locals, the deeper, more corrosive issue is human irresponsibility driven by capital. “We have businessmen in Dhaka who own the big hotels and restaurants on the island,” she says. “They are the ones monopolising the media narrative and the protests against government restrictions, not the locals.”

The sensationalised narrative around the island’s stray dogs, Ahmad argues, is a powerful distraction from the core environmental concerns. St. Martin’s Island has a problem of high dog population density, but the narrative of mass starvation is largely a myth. “We did our survey in January,” she explains. “And we found that 85% of the dogs were in good health. They are not starving. Yet, people focus on the 15% that look ‘emaciated’ or ‘mangy’ for the drama, for the social media sensation.”

The dog population spiked in many areas, including Dhaka, after the COVID-19 pandemic, she notes, when people started feeding them during the lockdown and never stopped. This population rise is directly proportional to unmanaged, open waste. On St. Martin’s Island specifically, the majority of this unrecyclable waste is coming from people visiting from outside.

Ahmad understands why people get defensive about it. “It’s like you’re taking something away from them,” she sighs, momentarily softening her intense focus. “This is the one thing they do for animals, and you’re saying they can’t do that.” She argues that while feeding a hungry animal seems like the immediate, ethical solution, on an island with zero population control or even in a maze-like city like Dhaka, this action, driven by goodwill, is actively making matters worse.

Rubaiya Ahmad insists that emotional goodwill is not enough. “Feeding an unsterilised population that doesn’t need it? It’s like pouring gasoline on the flame,” she says, citing the dire situation in other countries. “Look at the situation in Delhi now. The government has given up in many parts of India because they won’t stop feeding dogs. They are contributing to the problem, and then the burden falls on the state to clean it up.” She explains that such well-intentioned, unplanned feeding leads to ecological and government failure in several ways. Firstly, it harms the community’s sense of ownership and care; islanders had looked after these dogs for years before outsiders poured in with food, creating an unwanted dependency and a disconnect. Secondly, it is fundamentally unsustainable — how long can they keep raising funds to feed an ever-growing population? And finally, it disrupts the natural balance by creating a situation where the animals have to rely on somebody else for food.

The solution, she insists, cannot be individual charity; it must be a community responsibility. “We set up a club called Aar Deep, Aar Kukur (My Island, My Dog) to shift the ownership. You don’t have to come here from Dhaka to feed them. The local community must take care of them.” She advocates for an approach led by science, where the community raises funds to get them spayed and neutered. Dogs, she stresses, do not deserve to be locked up. “We can’t house or foster every dog, and that’s not what they deserve either. They should be safe to roam and live on our roads. But we must control their numbers first. That’s the real work.”

Obhoyaronno’s focus, in contrast, is on science-based, humane population control. Rubaiya Ahmad proudly reports a significant milestone on the island. “We have successfully vaccinated and sterilised 60% of the dog population,” she reveals. Every single sterilised dog has been microchipped, providing a verifiable, unarguable record of their work — a necessary defence against the local authorities who had previously attempted mass culling. The success of the CNVR programme, which has already led to locals reporting a calmer breeding season and a near absence of puppies, proves her scientific approach works. But the battle is constant. “The problem of St. Martin’s is not the dogs. The Island dogs are a very small part of the eco-system. It’s the people.”

People travel to this beautiful, fragile island only to perform the same detrimental behaviour they exhibit in their local neighbourhood park. “They call it their right,” She explains. “We think as taxpayers, we have the right to go and litter an island. This is who we are.”

The new restrictions introduced by the government for the reopening season attempt to curb that problem. The tourists need to keep in mind that St. Martin’s Island is not just a tourist destination. It is the permanent, fragile home to a delicate coral ecosystem, nesting sea turtles, and a local community. Tourists visiting this season must adopt the mindset of being a respectful guest in someone else’s house, where the rules, such as the ban on single-use plastics, the restriction on beach fires, entering the Keya fruit areas or operating motorised vehicles on the beach, are not arbitrary limitations, but essential house rules for the hosts’ survival and well-being. By limiting your footprint, adhering strictly to the daily visitor cap and coded entry, and prioritising silence and cleanliness, you show necessary deference to the natural inhabitants, ensuring that this unique, recovering sanctuary is not loved to death, but preserved for the future.

Ahmad believes that large-scale tourism and island conservation are fundamentally incompatible on an island this small and fragile. “Globally, you don’t find island-based mass tourism in such small geographical areas. If 8,000 people go there every day, they will exhaust it.” Her vision is radically different, and she advocates for research-based tourism. “For those who want to study marine biology, marine science. We have a fantastic marine museum. That is what will give the island financial stability without destruction.”

As I finished the strong tea, and the conversation turned from policy to public opinion, Rubaiya Ahmad offered a final opinion, “It’s a tough thing that people just have to hear. Learn something else. Do something that actually has an impact,” she insists. “Science is available. Listen to what experts are saying. This is what I’ve seen first-hand.”

I thanked her for the tea and the conversation. She smiled. “We don’t drink milk here, so we had to come up with an equally good alternative,” she shared, gesturing to the empty cup, before we said our goodbyes.