An exploration of how the global shift from gold-backed money to fiat currency reshaped the world economy.

For centuries, gold was the heartbeat of global wealth. Kings hoarded it, merchants trusted it, and ordinary people viewed it as the purest symbol of stability. Gold didn’t rely on anyone’s promise. It glittered, it endured, and it was universally accepted. But the world we live in today runs on something far less tangible — debt. To understand how every government in the world ended up owing trillions, we need to trace the extraordinary journey of money itself — from the shimmering vaults of gold to the invisible web of credit.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF “REAL” MONEY

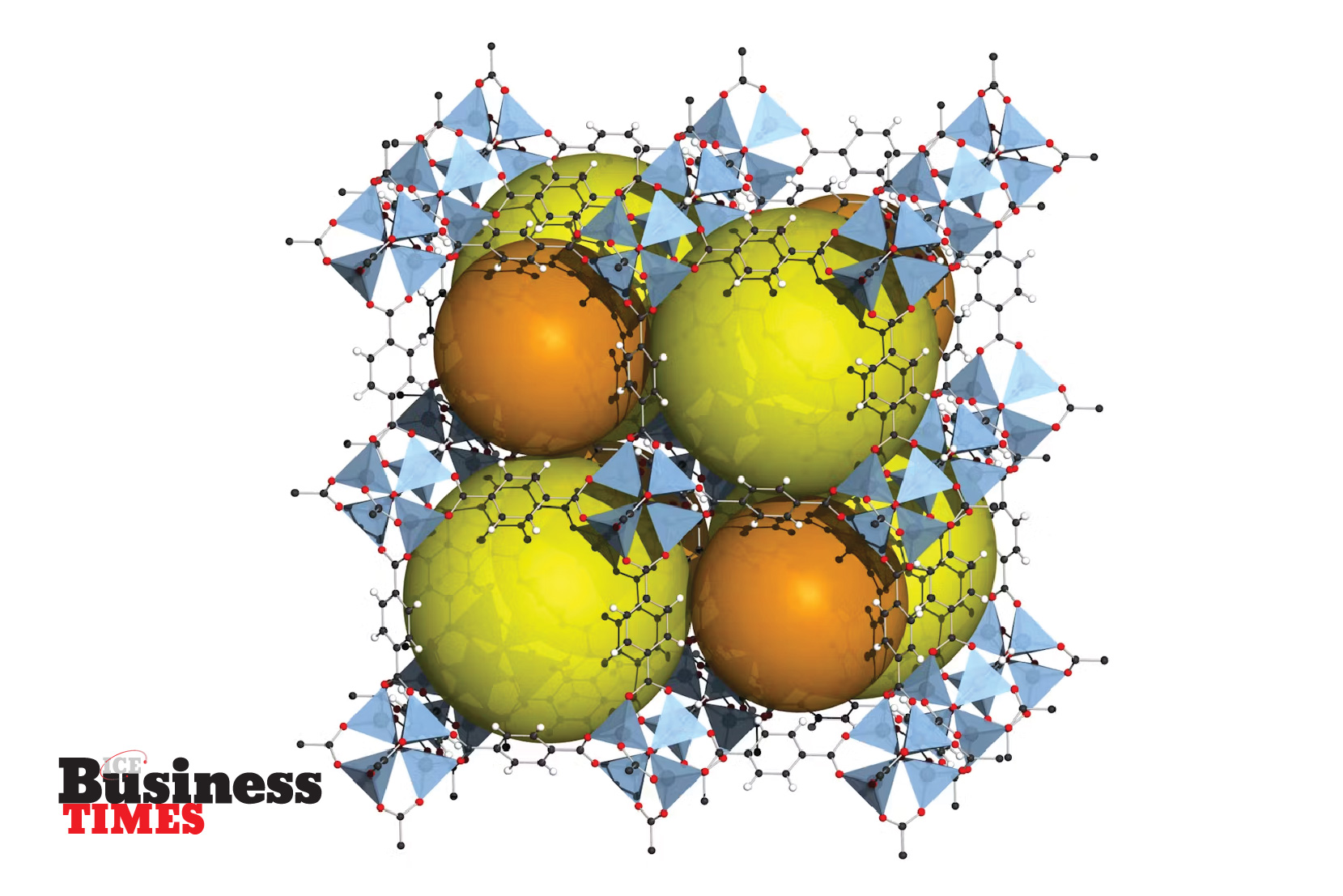

Long before banks and digital transfers, gold was money in its truest form. Gold coins made good currency because the metal was rare, durable, and impossible to counterfeit. However, as trade expanded across continents, merchants faced a problem: carrying gold was risky and inconvenient. To solve it, early bankers began issuing paper receipts for deposited gold. These receipts could be exchanged like money. The system worked because every piece of paper represented real gold stored safely in a vault. That idea evolved into what became known as the “gold standard” — a global agreement that every nation’s currency would be backed by a fixed amount of gold.

By the 19th century, the gold standard ruled international finance. The British pound, the American dollar, and the French franc were all tied to gold reserves. This created stability, as governments couldn’t print more money than they had gold. It kept inflation low and forced discipline on those in power. But that discipline came at a price: it made it hard for countries to react during crises.

LONG BEFORE BANKS AND DIGITAL TRANSFERS, GOLD WAS MONEY IN ITS TRUEST FORM. GOLD COINS MADE GOOD CURRENCY BECAUSE THE METAL WAS RARE, DURABLE, AND IMPOSSIBLE TO COUNTERFEIT.

THE BREAKING POINT

The first cracks appeared during World War I and widened during World War II. Nations needed to fund massive military efforts, but gold reserves in treasuries couldn’t keep up with wartime spending. So, governments began printing money beyond what their gold holdings allowed. Consequently, inflation rose, and the foundation of the gold standard began to crumble.

In 1944, the world’s major powers met in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to rebuild the post-war economy. They established a new order: the U.S. dollar, which would become the anchor of the global financial system. The United States, which then held more than two-thirds of the world’s gold, promised to convert dollars into gold at a fixed rate of USD 35 per ounce. Other nations pegged their currencies to the dollar, creating what became known as the Bretton Woods system. For a while, it restored confidence and stability, but by the late 1960s, the system began to falter again.

The U.S. government was spending heavily on the Vietnam War and its domestic programs while running large trade deficits. Dollars were flooding the world, but American gold reserves were shrinking. Foreign governments started demanding gold in exchange for their dollars, but the U.S. could no longer meet those requests.

Then came the turning point. On 15 August 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon went on television and announced that the dollar would no longer be convertible into gold. It was supposed to be a temporary measure, but it became permanent. That decision, known as the “Nixon Shock,” ended the gold standard once and for all.

From that day forward, money was no longer tied to anything physical. It became fiat money, meaning it had value simply because governments declared it to have value and because people continued to believe in it.

THE AGE OF DEBT BEGINS

The shift to fiat money gave governments enormous flexibility. No longer constrained by gold reserves, they could create money as needed to fund public spending, pay off debts, or stimulate growth. Central banks, such as the U.S. Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, could print new money or adjust interest rates to influence the economy. The only real limit was trust — as long as people and investors had confidence in a government’s ability to manage its currency, the system could function.

But this flexibility came with a hidden cost. In this new system, most money is created through debt. When governments spend more than they collect in taxes — which is almost always — they issue bonds, which are essentially IOUs promising to pay investors later with interest. These bonds are bought by individuals, banks, and even other governments. The borrowed money is then used for public projects, salaries, and programs. But to repay those loans, more borrowing often becomes necessary, creating a cycle that rarely ends.

In simple terms, modern economies are built not on gold reserves, but on promises to pay later.

THE SHIFT TO FIAT MONEY GAVE GOVERNMENTS ENORMOUS FLEXIBILITY. NO LONGER CONSTRAINED BY GOLD RESERVES, THEY COULD CREATE MONEY AS NEEDED TO FUND PUBLIC SPENDING, PAY OFF DEBTS, OR STIMULATE GROWTH.

A WORLD BUILT ON BORROWING

According to the U.S. Federal Reserve, the U.S. national debt has surpassed USD 36 trillion as of 2025, which is more than what the entire U.S. economy produces in a year. Twenty years ago, it was below USD 10 trillion. Other countries face similar realities. The World Bank reports that global debt, including that of governments, companies, and households, has reached a record USD 307 trillion — nearly three times the world’s total economic output. Japan’s public debt exceeds 250% of its GDP, while countries across Europe and Latin America carry debt loads that were once unimaginable. Even developing nations like Bangladesh are feeling the pressure. The IMF notes that Bangladesh’s external debt alone stands at over USD 103 billion, much of it borrowed to support infrastructure, power, and education. These are not signs of recklessness — they are symptoms of a global system where debt is the fuel that keeps economies running.

THE ILLUSION OF ENDLESS MONEY

Supporters of fiat money argue that debt is not always bad. Borrowing allows countries to invest in growth and respond to crises. During the 2008 financial meltdown, for instance, governments printed money and took on debt to prevent a total collapse. Again in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic froze the global economy, central banks around the world — from the U.S. Federal Reserve to the Bangladesh Bank — injected trillions into the system to keep it afloat.

But this approach creates what some economists call an “addiction to borrowing.” As Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon warned in a 2024 interview, “The ability to spend without constraint is not unlimited.” Ratings agencies are beginning to agree — in 2025, Moody’s downgraded the U.S. government’s credit rating, citing unsustainable debt levels and rising fiscal risks.

The uncomfortable truth is that our modern financial system requires constant borrowing just to stay alive. When governments borrow, they issue bonds. Investors buy those bonds with money they themselves borrowed from banks. The banks, in turn, get their money from central banks that create it electronically. In this loop, almost every dollar — from your savings account to a government loan — exists because someone, somewhere, went into debt.

THE PRICE WE PAY

The effects of this debt-based system touch everyone. Inflation quietly erodes the purchasing power of ordinary citizens, making groceries and housing more expensive. Rising interest costs eat into public budgets, leaving less for education, healthcare, and development. And when global markets lose confidence — as they did during crises in Greece, Sri Lanka, and Argentina — entire economies can collapse under the weight of what they owe.

Investors and central banks are turning back to gold. Even though it no longer backs currencies, countries are buying more of it as a safeguard against instability. The World Gold Council reports that global central banks purchased over 1,000 tonnes of gold in 2023 — the highest amount in modern history. It seems, after all these years, gold still symbolises the one thing modern money struggles to maintain: trust.

WHEN PROMISES REPLACE GOLD

The story of money is, at its core, the story of human trust. Gold anchored that trust in something tangible. Fiat money replaced that anchor with faith — faith in governments, central banks, and the belief that tomorrow will be better than today. For decades, that faith has sustained global prosperity. But it’s also left us in a fragile position: we now live in a world where almost every dollar, euro, or taka is a promise — and promises, unlike gold, can be broken.

As economist Nouriel Roubini once said, “The next crisis will not be about liquidity, but about solvency.” In simpler words, the danger isn’t running out of money — it’s running out of trust.

THE EFFECTS OF THIS DEBT-BASED SYSTEM TOUCH EVERYONE. INFLATION QUIETLY ERODES THE PURCHASING POWER OF ORDINARY CITIZENS, MAKING GROCERIES AND HOUSING MORE EXPENSIVE. RISING INTEREST COSTS EAT INTO PUBLIC BUDGETS, LEAVING LESS FOR EDUCATION, HEALTHCARE, AND DEVELOPMENT.

THE LEGACY OF A LOST STANDARD

From the shimmering coins of ancient markets to the endless digits of modern debt, money’s evolution tells a story of both human progress and fragility. We freed ourselves from the weight of gold, only to bind ourselves to the weight of promises. Governments can print paper, create credit, and move trillions with keystrokes, but they can’t print trust — and that, ultimately, is what keeps the system alive. Gold may no longer define our currencies, but it still reminds us of a time when value was real, not imagined. In a world of rising debt and fading confidence, perhaps the old metal’s greatest lesson is that true wealth is not in how much we can borrow, but in how much we can believe.