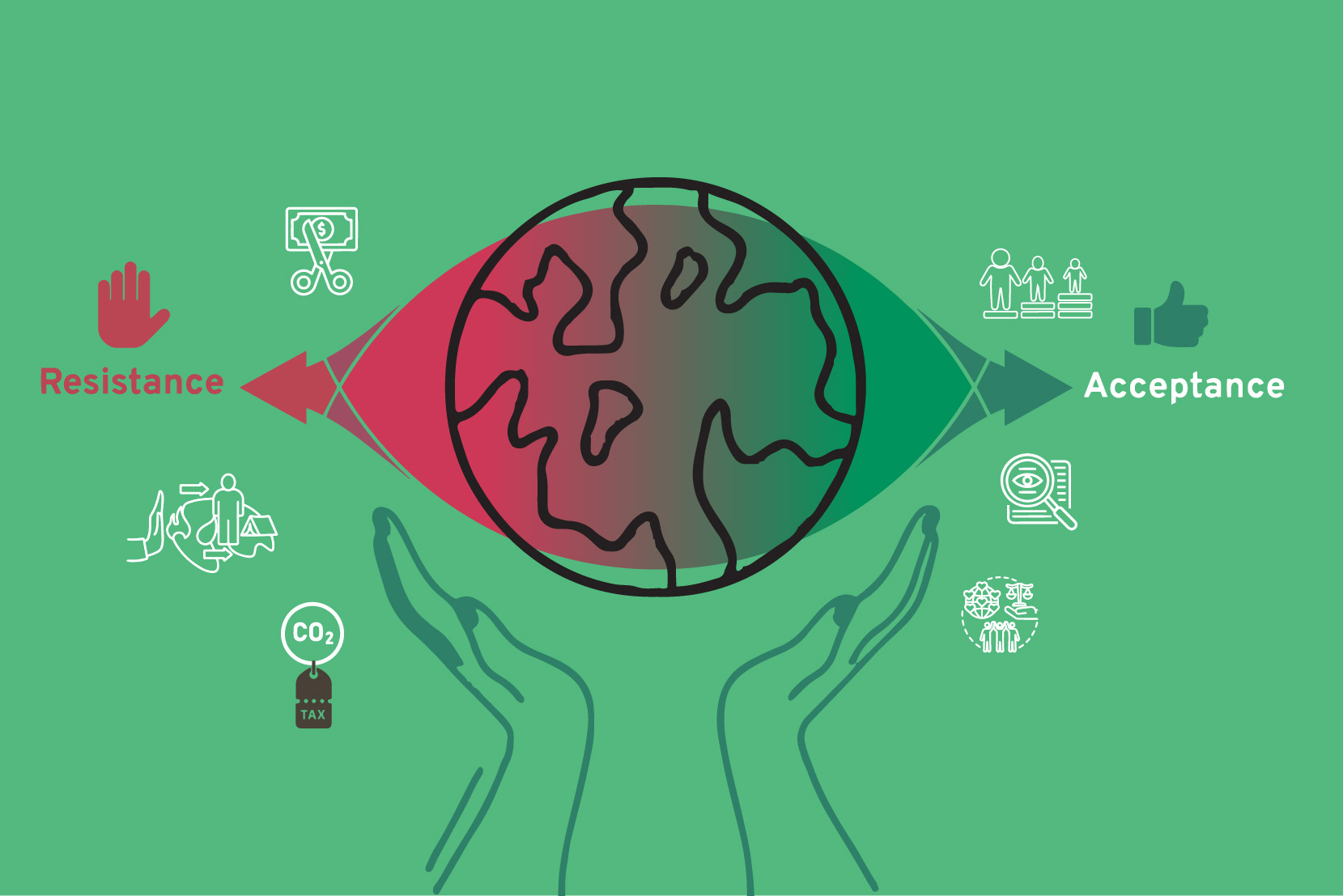

An approach to designing climate measures based on the perceived fairness of climate policies.

In recent research, perceived fairness has emerged as a pivotal factor in determining whether people embrace or resist climate policies. When citizens believe that the costs, such as higher fuel prices or new regulations, and the benefits, like cleaner air or better flood defences, are shared equitably across all segments of society, they are far more willing to support measures like carbon pricing, tighter emissions standards, or reformed subsidies. In concrete terms, fairness means that no single group, particularly the poorest or most vulnerable, is asked to shoulder an unfair share of the burden. Conversely, if a policy appears to place heavy costs on farmers, low-income families, or coastal communities while wealthier urbanites or large industries reap most of the gains, people will complain, protests may erupt, and politicians may be forced to roll back or dilute the measures. In Bangladesh, a country already grappling with extreme weather, rising sea levels, and entrenched inequality, these dynamics are especially critical. By ensuring that revenue from climate measures is used in transparent ways, involving communities in decision-making, and offering targeted support to those most at risk, policymakers can transform potential resistance into active support and lay the foundation for lasting, effective action.

Why Fairness Shapes Acceptance

Fairness is not just a moral ideal; it is a practical necessity for successful policy. Decades of social science research show that people’s judgments about whether a climate measure is ‘fair’ often carry more weight than their understanding of its technical merits. For instance, when a government introduces a carbon levy, a small extra charge on fuels like petrol or diesel, citizens ask two questions: Who pays the extra cost, and what happens to the money raised? If the answers are unclear or seem to favour the rich, scepticism grows. Yet when the same levy is accompanied by clear plans to channel revenues into health clinics in rural areas, improved drainage systems in flood-prone neighbourhoods, or direct cash benefits for low-income families, public approval can rise dramatically. In simple terms, people are more inclined to accept short-term sacrifices if they see that those sacrifices will be repaid in concrete, fair ways, especially when they benefit people like themselves. This human tendency to weigh fairness so heavily is why transparent, equitable design is the linchpin of climate policy acceptance.

Fairness Challenges in the Bangladeshi Context

Bangladesh’s social and economic landscape highlights the importance of fairness more starkly than in many places. With around twenty million people living under the official poverty line, many families depend on daily earnings from farming, fishing, or small-scale trading. A sudden increase in fuel costs, for example, can raise transportation prices and disrupt supply chains, hitting both producers and consumers. At the same time, longstanding subsidies on fossil fuels have disproportionately benefited urban industries and wealthier households that use more energy, while rural communities have received relatively little support. As a result, when talk turns to removing or reducing these subsidies to free up funds for green projects, many fear they will lose out while others gain. Surveys of young professionals and rural residents alike show that people understand Bangladesh faces serious climate threats, yet they worry that new climate taxes or levies will punish them unfairly. Without deliberate measures to address these concerns, such as compensating vulnerable groups or sharing savings in a visible way, proposals for cleaner energy and reduced emissions risk becoming politically toxic rather than transformative.

DECADES OF SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH SHOW THAT PEOPLE’S JUDGMENTS ABOUT WHETHER A CLIMATE MEASURE IS ‘FAIR’ OFTEN CARRY MORE WEIGHT THAN THEIR UNDERSTANDING OF ITS TECHNICAL MERITS.

Principles for Fair Climate Policy Design

To secure wide public backing, climate policies in Bangladesh must be built explicitly around a set of fairness principles. First, revenue transparency is essential. If the government introduces a small extra charge on fuels or a modest levy on carbon emissions, it should simultaneously launch a public information campaign explaining exactly how the collected funds will be spent, whether on community flood defences, solar energy grants for families, or health-care improvements in coastal villages. Regular reports and open audits can reinforce trust and show that promises are kept. Second, policies should distribute costs progressively, meaning that those who use more energy or have higher incomes bear a larger share of the burden. For example, a tiered electricity tariff can allow basic household use at an affordable rate while charging higher rates for heavy industrial users. Third, decision-making processes must be inclusive. By creating local committees that include farmers, fishers, slum dwellers, women’s associations, and business representatives, the government can ensure that diverse voices shape climate measures from the outset. This not only improves policy design but also fosters a sense of ownership, reducing the likelihood of opposition. Fourth, targeted support for those directly affected, such as retraining programs for workers in polluting industries or microcredit for small farmers upgrading to climate-smart techniques, signals that the state is committed to social justice alongside environmental goals. Finally, a sustained communication drive using radio broadcasts in rural areas, television programs, social-media campaigns for younger audiences, and community workshops can explain both the environmental need for action and the fairness elements built into each policy, correcting misunderstandings and building broad-based trust.

Applying Fairness to Priority Policies in Bangladesh

Putting fairness into practice can transform specific policy areas. Consider a modest fuel-price levy: by ring-fencing the revenue for rural electrification projects or cyclone shelters in the most vulnerable districts, the government can show immediate benefits to communities at risk. When fossil-fuel subsidies are phased out, a parallel ‘resilience grant’ program for smallholder farmers and urban poor households ensures that savings are recycled to those who need them most, rather than disappearing into general government coffers. In renewable energy, sliding-scale subsidies for solar home systems or biogas digesters can guarantee that low-income rural families receive the deepest discounts, preventing the benefits from skewing toward wealthier urban adopters. Urban climate resilience investments, such as improved drainage channels, early-warning flood systems, and green public spaces, should be co-designed with residents of low-lying neighbourhoods so that resources address local priorities, expectations are managed, and projects reflect community needs. Each of these examples becomes more politically and socially sustainable when people understand how they will personally benefit, and when they feel their voices have shaped the outcome.

BANGLADESH’S SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC LANDSCAPE HIGHLIGHTS THE IMPORTANCE OF FAIRNESS MORE STARKLY THAN IN MANY PLACES. WITH AROUND TWENTY MILLION PEOPLE LIVING UNDER THE OFFICIAL POVERTY LINE, MANY FAMILIES DEPEND ON DAILY EARNINGS FROM FARMING, FISHING, OR SMALL-SCALE TRADING.

Embracing Fairness for Effective Climate Action

Perceptions of fairness are far from a peripheral concern; they are decisive factors that can determine whether climate policies succeed or fail in Bangladesh. By embedding transparent revenue use, progressive burden sharing, participatory governance, targeted support, and robust communication into every stage of policy design and implementation, policymakers can align environmental objectives with social justice imperatives. This approach not only defuses potential backlash but also taps into Bangladesh’s collective spirit and resilience, qualities that have enabled the country to face past challenges from devastating cyclones to economic shocks. A truly just transition will turn people from reluctant observers into active partners, ensuring that Bangladesh not only meets its climate goals but does so in a way that uplifts and unites its communities, paving the way for sustainable prosperity in the years to come.