Exploring the Possible Impact of Bangladesh’s Graduation from an LDC

By Dr. Khondaker G Moazzem &

Kishore Kumer Basak

Dr. Khondaker G Moazzem is the Additional Research Director and Kishore Kumer Basak is the Senior Research Associate of the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). The paper was presented in a seminar organized by Bangladesh-Canada Chamber of Commerce and Industry in 2014. IBT is printing with permission from the authors. For further queries, please contact: Dr Khondaker G Moazzem at moazzemcpd@gmail.com.

Over the last decade, the growing bilateral trade with major developed and developing countries, including Canada, has significantly contributed to the development of Bangladesh. With a GDP growth rate of 6%+ over the decade, Bangladesh’s per capita income has reached US$1,054, which has helped reduce the poverty levels during the same period. As a result, Bangladesh has nearly reached the minimum threshold level for becoming a lower middle-income country. Since other major economic indicators (such as economic vulnerability and human resource related indicators) are improving Bangladesh’s graduation from LDC to a developing country would be possible in the near future. Graduation from an LDC to a developing country not only raises country’s pride but it bears costs as well. Canada’s preferential market access provided to LDCs would no longer be valid for Bangladesh as the country graduates from the LDC category, which would bring changes in Bangladesh’s trade relationship with Canada.

CANADA’S POSITION IN BANGLADESH’S INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Bangladesh’s international trade has made significant progress during the last decade – from US$13.9 billion in 2002 to US$43.9 billion in 2010. During this period, Canada has emerged as a major trading partner and has become the seventh largest export destination for Bangladesh (3.7% of Bangladesh’s total export in FY2014). Import from Canada has also increased which made it Bangladesh’s 18th largest source (with 1.9% of Bangladesh’s total import in FY2011). From the perspective of Canada, Bangladesh is yet to emerge as an important source of Canada’s import. Out of Canada’s total import of US$461.8 billion, Bangladesh’s share was only 0.25% during 2013.

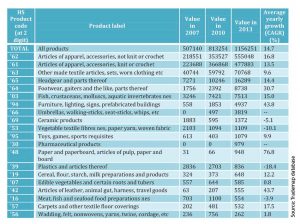

Bangladesh’s export to Canada has significantly improved in the 2000s particularly because of the Generalized Scheme of Preference (GSP) facility for LDCs (Table 1). In fact, the Canadian GSP is often ‘referred’ as most favorable for the promotion of LDCs’ export because of having flexible rules of origin (RoO) with only 25% of local value addition. Before the introduction of this GSP scheme, Bangladesh’s total export to Canada was less than US$100 million throughout the 1990s (only 125.7 million in 2001 which was only 1.9 per cent of Bangladesh’s total trade). With the support of preferential market access Bangladesh has been able to increase its export over to US$1.0 billion within a decade (US$1.3 billion in 2013 with a market share of 3.7 per cent of total export in FY0215).

Although Bangladesh’s overall export has accelerated in the Canadian market it was not diversified rather concentrated to a limited number of products (Table1). Apparels are accounted for about 90 per cent of Bangladesh’s export to the Canadian market. The export basket has been concentrated with fewer items over the years.

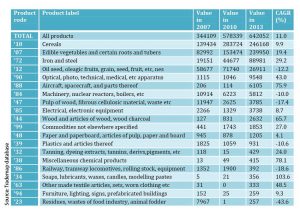

Import has significantly increased during the last decade as well; however, this rise has little relation with the rise in export (Table 2). Between 2002 and 2013, import has increased from US$44.5 million to US$ 642.1 million because of Canada’s growing importance to Bangladesh as a major source for some products.

ANALYSIS OF CANADA’S TARIFF STRUCTURE

Canada’s import tariff structure has evolved over the year in pursuant with its national demand. As a result, the average Most Favored Nation (MFN) applied rates varies from as low as 0% (for cotton) to as high as 248.9% (for dairy products) (Table 3). Clothing which is Bangladesh’s major export product to Canada faces a tariff of 16.5%. Since Canada provides duty-free market access under different agreements and arrangements to the developed and developing countries including LDCs, a large share of imported products enjoy zero duty. The highest share of products imported under zero duty is cotton (100%) followed by petroleum (98.0%), non-electrical machinery (95.8%) and minerals and metals (86.9%). This indicates that Bangladesh has yet to develop its competitiveness beyond a limited number of products (mostly apparels) to take the advantage of duty-free market access, which other countries have been doing.

Table 1: Bangladesh’s export to Canada (‘000 $)

Table 2: Bangladesh’s import from Canada (‘000 $)

BANGLADESH’S GRADUATION FROM LDCS: POSSIBLE IMPLICATIONS ON ITS EXPORT TO CANADA

According to Canada’s GSP scheme for LDCs, countries would not be entitled to the benefits of duty-free market access if it graduates from its LDC status. By becoming a developing country, import from Bangladesh would face the MFN rates, which are applicable for other developing countries. As mentioned earlier, Canada’s MFN tariff rates widely vary from 0% to over 240% depending on the products. Hence, a loss of entitlement of duty-free market access would imply facing the applicable MFN tariff rates.

Table 3: Import Tariffs in the Canadian Market (2013)

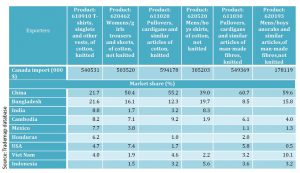

Table 4: Bangladesh’s Major Competing Countries in the Canadian Market and Their Market Share (%) in Selected Set of Products

Among Bangladesh’s top twenty export items to Canada, which comprise about 72% of Bangladesh’s export- sixteen products have MFN tariff rates of 17-18%, one product has tariff rate of 9% and two products have 0%. In other words, Bangladesh is currently enjoying preference margin of 9% of these products over products of non-LDC countries. Analysis of top export products reveals that Bangladesh is the second most important import source after China in the Canadian market (Table 4). Bangladesh’s market share comprises between 8% and 22% while China has a market share between 22% and 60%. Other competing countries with a considerable share include India (2% to 9%), Cambodia (2% to 9%), USA (1% to 7%) and Vietnam (2% to 10%). Bangladesh’s competitors include both developed, developing and LDCs a number of them enjoy preferential schemes at different levels.

Now, if Bangladesh graduates from its LDC status it has to provide MFN tariff rate. This MFN tariff rate will be higher than that of LDC and non-LDC enjoyed which enjoy preferential tariff. Under the new situation, Bangladesh’s competition in the market would increase where LDCs and other non-LDCs would become more competitive. This would make it difficult for local exporters to maintain their competitiveness. In a dynamic point of view, this would further narrow down exporting countries’ utilization of their export potentials in major markets like Canada.

The extent of impact on Bangladesh’s export will depend on what kinds of bilateral trade agreements and arrangements Canada has with Bangladesh’s competing countries. Canada has bilateral free trade agreements with 12 countries/group of countries. It is currently negotiating with 10 countries/group of countries for signing a Free Trade Agreement (FTA). It has recently completed discussions on bilateral FTA with the EU. A number of Bangladesh’s competing countries either are members of existing FTAs or would become the members. Hence, Bangladesh’s export is likely to face further competition even under its existing LDC status. The competition would be fiercer when Bangladesh will not have LDC status. However, the preference margin would gradually reduce due to slow reduction of MFN rates particularly of manufactured products, which partly reduce the competitive advantage of countries enjoying duty-free market access facility.

Overall, Bangladesh’s export to Canada would face adverse competition when it does not have duty-free market access facility. Hence, it would be difficult to maintain the growth within its existing export items.

BANGLADESH’S PREPAREDNESS WITH REGARD TO GRADUATION FROM LDC STATUS

Analysis of Bangladesh-Canada bilateral trade shows that Bangladesh’s export to Canada may face adverse consequences when it is no longer an LDC. This analysis could be an appropriate test case to understand the possible impact of Bangladesh’s graduation from LDC on its bilateral trade with developed and developing countries. Since Bangladesh is likely to be adversely affected while it loses its LDC status, it needs to take precautionary measures and should be prepared.

a) Detailed analysis on possible implications on Bangladesh’s export: Bangladesh government should undertake a detailed product-wise analysis to appreciate the possible adverse impact on export due to loss of duty-free market access facility in the Canadian market. Such an analysis would help in the understanding of the nature and extent of impact on Bangladesh’s export with a view to set strategies for bilateral trade negotiations.

b) Identify the suitable strategies to deal with these issues: With the understanding on the nature and extent of possible impact on bilateral trade, Bangladesh needs to identify strategies to accommodate the situation. First, Bangladesh should identify a list of products where it needs preferential scheme most, followed by another list of products where the preferential scheme is also important. Second, Bangladesh needs to address these issues with the Canadian government and request for a favorable preferential market access scheme. Third, Bangladesh needs to identify products where MFN rates are zero and would not have any implications in the tariff rates after its graduation from LDCs. Since trade potentials for such products are found to be high, putting an emphasis on enhancing their export capacities would be equally important.

c) Finding strategies for enhancing productivity: Bangladesh needs to improve its productivity in order to maintain its competitiveness over other developing countries. Hence, Bangladesh should take sector-specific measures to improve its productivity and efficiency, which will help reduce production costs and make local products competitive in the Canadian market.